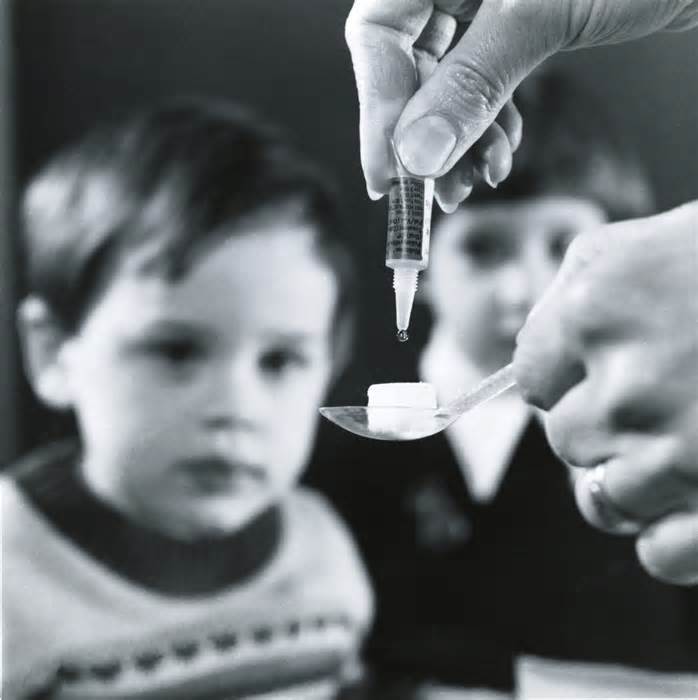

Child vaccination rates fell into harmful territory in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, when schools closed and most doctors treated emergency patients.

But instead of recovering after schools reopen in 2021, traditionally low rates have worsened, according to new knowledge from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. a contribution to the decline.

According to today’s data, the percentage of American children entering kindergarten with required vaccinations dropped to 93% in the 2021-22 school year, the 2% age is below herd immunity levels of 95% and below vaccination rates in 2020-21, when many schools and doctors’ offices were closed.

“While one percentage point of age may not sound concerning, that 1 percent represents tens of thousands of children who are not adequately from diseases that we can easily save through vaccination,” said Dr. Brown. Michelle Fiscus, medical director of the Association of Immunization Managers, a nonprofit organization of state officials who lead vaccination efforts.

“This national trend is alarming, especially as we see measles outbreaks in Ohio among young people who are too young to be vaccinated and among those who are not adequately vaccinated. We want everyone to be on the lookout for those young people,” Fiscus said.

Public health officials warn that unless vaccination rates for formative years against measles, chickenpox, polio and other diseases temporarily return to pre-pandemic levels, outbreaks of preventable diseases, such as measles outbreaks in Ohio and Minnesota in the fall and the polio case in New York City last summer, Most likely, it is commonplace.

While COVID-related disruptions in schools and the fitness formula are arguably the primary cause of this recent drop in vaccination rates, they are only one component of explaining why state-required vaccination rates tend to decline, according to public fitness experts. .

They say the politicization of public health and the development of distrust of government have skewed parents’ positive attitudes in the past toward vaccines against measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox, tetanus, diphtheria, polio and other formative years diseases that have been virtually eradicated.

“I’m shaking with anxiety about this,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. It meant that the existing generation of moms and dads knows little or nothing about those diseases.

“If you’re not concerned about the disease and don’t adhere to vaccines,” he added, “you can’t abide by state legislation that requires them. “

Overall, public willingness to stick to public fitness needs has declined since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Dr. Marcus Plescia, medical director of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers.

The political divide that has erupted over quarantines, mask wearing and COVID vaccines, he said, could impact what has been a widely accepted public policy protecting young people from infectious diseases.

In 2019, a measles outbreak in a single person of 72 cases in Washington state claimed $3. 4 million, according to estimates by CDC researchers, with maximum costs borne by local public fitness agencies.

State vaccination rates vary widely. For the 2021-22 school year, Alaska, the District of Columbia, Wisconsin, Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky and Ohio had the lowest rates. New York, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Delaware, California, Massachusetts and Nebraska had the rates.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia require children to be vaccinated against diseases from formative years before entering kindergarten, whether in a public or private school. Each state allows medical exceptions and allows parents to apply for a waiver for philosophical or philosophical reasons.

Public health officials say the way states can increase vaccination rates for their youth is to enact strict vaccination mandates without exception except for medical reasons, such as for young people undergoing cancer treatment.

Mississippi and West Virginia, which have such strict vaccination mandates, have had vaccination rates in the country for decades.

California eliminated its non-medical vaccine exemptions in 2015, followed by Maine and New York in 2019 and Connecticut in 2021. West Virginia’s vaccination mandate never included non-medical exemptions, and Mississippi law eliminated non-medical exemptions in 1979 after the state Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional.

California repealed its non-medical exemptions in reaction to high-profile measles outbreaks in 2014 and 2015, adding one that began at Disneyland. After the law went into effect, the policy for measles, mumps and rubella increased to 3. 3%, bringing California closer to the herd immunity vaccination threshold of 95% against measles.

With maximum state vaccination mandates established in the 1980s, the CDC declared victory over measles in 2000.

But in years, the number of diagnoses has increased: In 2014, 667 cases of measles were reported to the CDC. In 2019, state fitness departments reported 1274 cases of measles.

Even so, immunization rates in the formative years in the United States remained at a high compared to other developed countries, and public attitudes toward the vaccine regimen for the formative years were positive.

But since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, state vaccination requirements have been met with more opposition. In October, a vote by the Harvard Opinion Research Program showed vaccination requirements for school entry dropped to 74 percent, down from 84 percent. in 2019.

A similar survey released through the Kaiser Family Foundation in November showed that 28% of respondents said parents can refuse to vaccinate their school-age children, even if it poses a health hazard to others.

That’s up from just 16% who responded in a 2019 survey conducted through the Pew Research Center. (The Pew Charitable Trusts run the outlet and Stateline News. )

Over the past two years, dozens of expenses were proposed that would cause parents to opt out of the vaccination regimen for their school-age children, as well as COVID-19 shots, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, which follows state legislation.

In 2021, Kentucky and Florida enacted laws allowing parents to opt out of the vaccination regimen while enrolling their children in school.

In addition to tightening vaccination mandates, public health officials say some states want to improve their regulations and increase education and online messaging, so parents better perceive the importance of vaccinating their children.

Measles, for example, is much more contagious than COVID-19. It infects nine out of 10 people an inflamed user encounters, and contagion can persist in a room for at least two hours after an inflamed user leaves.

Although most cases of measles disappear within a week, it is a life-threatening respiratory illness that affects hospitalization. In Ohio, for example, 33 of the 82 children with measles last year were hospitalized.

Dr. Anne Zink, lead medical officer for the Alaska Department of Health and president of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said access to pediatricians, family doctors and other fitness professionals who can administer vaccines for formative years is another way states are having more children. Vaccinated.

Pediatricians and family circle doctors usually give vaccines to young people 12 to 23 months of age. local communities.

Matt Guido, Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel’s study coordinator in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, said states deserve to leverage established infrastructure to push COVID-19 vaccines and engage some members of the same community. Leaders to help parents vaccinate their children before they start school next year.

This story was written and produced through Stateline News, which legalized its republication. The original article can be found here.

by Christine Vestal, Quotidien Montanan 22 January 2023

Child vaccination rates fell into harmful territory in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, when schools closed and most doctors treated emergency patients.

But instead of recovering after schools reopen in 2021, traditionally low rates have worsened, according to new knowledge from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. a contribution to the decline.

According to today’s data, the percentage of American children entering kindergarten with required vaccinations dropped to 93% in the 2021-22 school year, the 2% age is below herd immunity levels of 95% and below vaccination rates in 2020-21, when many schools and doctors’ offices were closed.

“While one percentage point of age may not sound concerning, that 1 percent represents tens of thousands of children who are not adequately from diseases that we can easily save through vaccination,” said Dr. Brown. Michelle Fiscus, medical director of the Association of Immunization Managers, a nonprofit organization of state officials who lead vaccination efforts.

“This national trend is alarming, especially as we see measles outbreaks in Ohio among young people who are too young to be vaccinated and among those who are not adequately vaccinated. We want everyone to be on the lookout for those young people,” Fiscus said.

Public health officials warn that unless vaccination rates for formative years against measles, chickenpox, polio and other diseases temporarily return to pre-pandemic levels, outbreaks of preventable diseases, such as measles outbreaks in Ohio and Minnesota in the fall and the polio case in New York City last summer, Most likely, it is commonplace.

While COVID-related school disruptions and fitnesscare’s formula are arguably the number one cause of this recent drop in vaccination rates, they are only one component of explaining why state-mandated vaccination rates are trending downward, according to public fitness experts.

They say the politicization of public health and the development of distrust of government have skewed parents’ positive attitudes in the past toward vaccines against measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox, tetanus, diphtheria, polio and other formative years diseases that have been virtually eradicated.

“I’m shaking with anxiety about this,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. It meant that the existing generation of moms and dads knows little or nothing about those diseases.

“If you’re not concerned about the disease and don’t adhere to vaccines,” he added, “you can’t abide by state legislation that requires them. “

Overall, public willingness to stick to public fitness needs has declined since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Dr. Marcus Plescia, medical director of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers.

The political divide that has erupted over quarantines, mask wearing and COVID vaccines, he said, could impact what has been a widely accepted public policy protecting young people from infectious diseases.

In 2019, a measles outbreak in a single person of 72 cases in Washington state claimed $3. 4 million, according to estimates by CDC researchers, with maximum costs borne by local public fitness agencies.

State vaccination rates vary widely. For the 2021-22 school year, Alaska, the District of Columbia, Wisconsin, Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky and Ohio had the lowest rates. New York, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Delaware, California, Massachusetts and Nebraska had the rates.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia require children to be vaccinated against diseases from formative years before entering kindergarten, whether in a public or private school. Each state allows medical exceptions and allows parents to apply for a waiver for philosophical or philosophical reasons.

Public health officials say the way states can increase vaccination rates for their youth is to enact strict vaccination mandates without exception except for medical reasons, such as for young people undergoing cancer treatment.

Mississippi and West Virginia, which have such strict vaccination mandates, have had vaccination rates in the country for decades.

California eliminated its non-medical vaccine exemptions in 2015, followed by Maine and New York in 2019 and Connecticut in 2021. West Virginia’s vaccination mandate never included non-medical exemptions, and Mississippi law eliminated non-medical exemptions in 1979 after the state Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional.

California repealed its non-medical exemptions in reaction to high-profile measles outbreaks in 2014 and 2015, adding one that began at Disneyland. After the law went into effect, the policy for measles, mumps and rubella increased to 3. 3%, bringing California closer to the herd immunity vaccination threshold of 95% against measles.

With maximum state vaccination mandates established in the 1980s, the CDC declared victory over measles in 2000.

But in years, the number of diagnoses has increased: In 2014, 667 cases of measles were reported to the CDC. In 2019, state fitness departments reported 1274 cases of measles.

Even so, immunization rates in the formative years in the United States remained at a high compared to other developed countries, and public attitudes toward the vaccine regimen for the formative years were positive.

But since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, state vaccination requirements have been met with more opposition. In October, a vote by the Harvard Opinion Research Program showed vaccination requirements for school entry dropped to 74 percent, down from 84 percent. in 2019.

A similar survey released through the Kaiser Family Foundation in November showed that 28% of respondents said parents can refuse to vaccinate their school-age children, even if it poses a health hazard to others.

That’s up from just 16% who responded in a 2019 survey conducted through the Pew Research Center. (The Pew Charitable Trusts run the outlet and Stateline News. )

Over the past two years, dozens of expenses were proposed that would cause parents to opt out of the vaccination regimen for their school-age children, as well as COVID-19 shots, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, which follows state legislation.

In 2021, Kentucky and Florida enacted laws allowing parents to opt out of the vaccination regimen while enrolling their children in school.

In addition to tightening vaccination mandates, public health officials say some states want to improve their regulations and increase education and online messaging, so parents better perceive the importance of vaccinating their children.

Measles, for example, is much more contagious than COVID-19. It infects nine out of 10 people an inflamed user encounters, and contagion can persist in a room for at least two hours after an inflamed user leaves.

Although most cases of measles disappear within a week, it is a life-threatening respiratory illness that affects hospitalization. In Ohio, for example, 33 of the 82 children with measles last year were hospitalized.

Dr. Anne Zink, lead medical officer for the Alaska Department of Health and president of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said access to pediatricians, family doctors and other fitness professionals who can administer vaccines for formative years is another way states are having more children. Vaccinated.

Pediatricians and family circle doctors usually give vaccines to young people 12 to 23 months of age. local communities.

Matt Guido, Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel’s study coordinator in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, said states deserve to leverage established infrastructure to push COVID-19 vaccines and engage some members of the same community. Leaders to help parents vaccinate their children before they start school next year.

This story was written and produced through Stateline News, which legalized its republication. The original article can be found here.

Daily Montanan belongs to States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported through grants and a coalition of donors such as a public charity 501c(3). Daily Montanan maintains its editorial independence. Please contact editor Darrell Ehrlick if you have any questions: info@dailymontanan. com. Follow Daily Montanan on Facebook and Twitter.

Christine Vestal covers intellectual fitness and addictions for Stateline. Prior to joining Pew, he covered physical health care, environment, energy, data generation, and telecommunications for various media outlets, including McGraw-Hill, Financial Times, and Post-Newsweek Business Information. At Stateline, she covered legal and political battles over the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion to more low-income adults. The epidemic of prescription painkillers and heroin, adding efforts to stop overdose deaths by making the drug addiction remedy more available.

DEMOCRACY TOOLBOX

The Daily Montanan is a nonpartisan, nonprofit source of data, commentary, and reliable data on state policy and Big Sky politics.

Our stories can be republished online or republished under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4. 0 license. We ask that you modify them to suit taste or shorten them, provide appropriate attribution and a link to our website.