Advertising

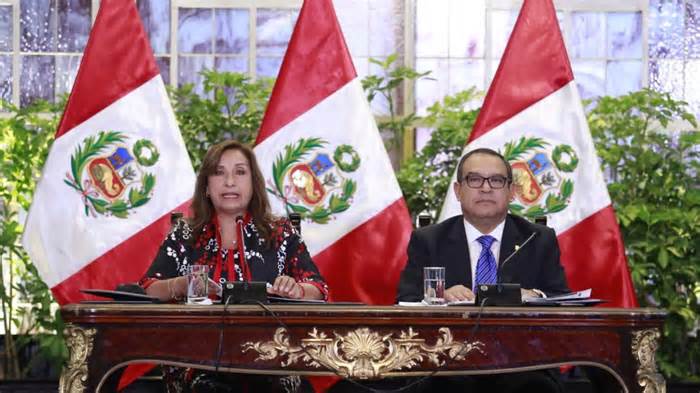

Peruvian President Dina Boluarte speaks in a televised speech. Photo courtesy of the Presidency of Peru/X.

It’s been just over a year since Dina Boluarte assumed the presidency of Peru, but she’s wasting no time in making big adjustments to attract foreign investment and ensure the expansion of commercial mining in the country.

Following the impeachment and arrest of former President Pedro Castillo on Dec. 7, 2022, Boluarte — then vice president — assumed the highest office, even as protests called for her resignation and the holding of new general elections.

The South American country is now in the midst of a major democratic crisis, having gone through five presidents in three years. Between December 2022 and February 2023, when police cracked down on protestors, more than 1,200 were injured and at least 49 killed, according to Amnesty International.

Since then, Boluarte has consolidated her strength and intensified her efforts to attract foreign mining investment. The administration has also pushed through reforms to replace the way disputed mining projects are approved in the country.

In November, the government presented the “United Plan,” a multi-sector strategy for post-pandemic economic expansion that aims to expedite the granting of mining permits and designates the advancement of seven mining projects as economic priorities. Boluarte issued an executive decree aimed at accelerating the granting of water concessions at mines, in addition to several other reforms already underway that, according to the Minister of Energy and Mines, aim to “unlock mining projects and attract more investment. “

According to Red Muqui, a network of Peruvian organizations fighting for human rights and sustainable development, “mining associations have embarked on an unprecedented communication crusade to facilitate the administrative facets of mining – what the business sector calls ‘mining bureaucracy’ – in order to accelerate increase projects, merge environmental agencies, needs and decrease environmental monitoring. In a recent public statement, the organization said, “The industry seeks to explode anywhere and as quickly as possible, with limited participation from [affected] people. “

More than 70 Canadian mining corporations are currently active in Peru. Together, they have around $10 billion in assets, representing 4. 5% of Peru’s GDP in 2021. With the rise of the Boluarte regime, which is more favorable to the mining sector, those corporations see a wonderful opportunity. .

Even as Peru was in the midst of an unfolding political crisis in early 2023 and thousands of Peruvians were facing police violence as they protested in the streets, Canadian Embassy officials were meeting with mining industry associations and Peruvian officials to announce increased Canadian mining investment in the country. The embassy has only intensified its public relations crusade in the year since Boluarte came to power.

Louis Marcotte, Canada’s ambassador to Peru and Bolivia, participated in interviews with local media to publicize the industry and hail Peru as a strategic mining partner, while the Embassy deployed infographics and other fabrics on social media to describe how Canadian mining corporations are making life imaginable. in Peru: from the production of the metals that power electric cars to the extraction of key ingredients from products ranging from household cleaning products to video game consoles.

Boluarte’s Plan Unidos would possibly see the mining sector as a catalyst to revive the economy, but efforts to attract mining investment to the country are not new. Even before the pandemic, previous governments promoted investments in lithium and copper mining as a way to make some economic expansion through capitalizing on the global energy transition.

Canada maintains that both countries stand to benefit from expanded extractive activities, emphasizing that while Peru possesses vast reserves of copper, lithium, zinc, and rare-earth minerals, Canadian companies have the knowledge in “climate-smart and sustainable mining” to get the resources out of the ground.

This year, Peru was again named a “Sponsor of a Mining Country” at the annual industry exhibition of the Association of Prospectors and Developers of Canada (PDAC), the world’s largest mining exploration and progression conference, held in downtown Toronto. The Ministry of Energy and Mines will use its platform at PDAC 2024, which brings together tens of thousands of industry and government representatives, to showcase the country’s most recent and planned mining reforms, with the aim of making Peru a popular destination for Canadian mining capital.

But the culmination of Peru’s mining-friendly policies is not shared equitably. As is the case throughout Latin America, the majority of the population – and its environs – are subordinated to the interests and profits of a transnational mining elite.

The southern province of Puno, near the border with Bolivia, is home to many mining operations, some in the exploration phase and others that have already started production. During the nationwide protests in early 2023, Puno was the scene of severe police repression. As indigenous and peasant communities came together to call for reforms to address the toxic environmental liabilities left by existing projects. They also called on Boluarte’s government to respect their right to consent to long-term projects through a community-based, transparent and fair pathway. Processes.

Downplaying the police violence and seeking to distance himself from the harsh protests of the citizen organization in Puno, Boluarte said at the time: “Puno is not Peru. ” This led Red Muqui to ask the question: “If Puno is not Peru, who owns it?” Lithium? And who is to blame for solving the related social, environmental, economic and health problems?

More Canadian mines appear to be on the horizon for Puno. Vancouver-based Bear Creek Mining’s Corani silver assets designated in Plan Unidos as one of the government’s seven priority projects, even though it failed to discharge the free, prior and informed consent of affected indigenous communities.

Two other Canadian concessions in Puno are the Macusani and Falchani lithium and uranium projects, which grow around and above the Quelccaya ice sheet, the second-largest glacial domain in the tropics. As documented through the Environmental Justice Atlas and MiningWatch Canada, local communities and organizations in Puno have condemned the lack of transparency around the two projects, the lack of regulatory frameworks to properly manage the mines, and the potential risks to public health and the environment, adding up to the greatest risks to public health and the environment. dangers to archaeological sites, adding cave paintings. There are also considerations that American Lithium Corp. (another Vancouver-based company) and the governments of Canada and Peru are transitioning power to market those mines as “green,” despite the fact that the concessions encroach on a fragile glacial ecosystem that serves as a key source of water and climate regulator.

For Red Muqui, prioritizing the profits of transnational corporations and accelerating large-scale extractive projects goes against the genuine wishes of the population at a time of intersecting crises:

Viviana Herrera is the Latin America program coordinator at MiningWatch Canada.

More than 75% of our operating budget comes back to us in the form of donations from our readers. These donations pay for our expenses and the fees of some of our writers, photographers, and graphic designers. Our followers are part of everything we do.

Advertisement

Advertising

Advertising

More than 75% of our operating budget comes back to us in the form of donations from our readers. These donations pay for our expenses and the fees of some of our writers, photographers, and graphic designers. Our followers are part of everything we do.

Subscribe to our email newsletter and receive our news and analysis.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada.