[The captions of the long-term photographs above and below are designed according to the artist’s insistence].

Few young artists have attracted as much attention as Cameron Rowland.They are not yet 35 years old, won a $625,000 MacArthur “genius” scholarship and the first Nomura Emerging prize of $100,000 in 2019, and their paintings are now at the Museum of Modern Art.Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago.But Rowland’s theme is complicated and thorny, and is said to be at odds with such fame.They sometimes focus on how everyday elements (furniture, design elements) make other stories of systemic racism visible, and are more involved with concepts than aesthetics.

However, every time Rowland organizes a new exhibition, it is an event and eventually his paintings landed in the UK before this year. Rowland’s new show, “3-4 Will.” IV v. 73 ” opened at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London (ICA) in January, and the museum promised that it would be back in sight once the coronavirus blockade was completed. As with Rowland’s other efforts, it is an intellectual company. The ICA The exhibition area is almost completely empty and there is no text on the wall or declaration of preservation. Instead, visitors get a 19-page flyer to navigate the gallery. If you have the energy and patience to read an essay with many annotations, Rowland explains the theme of the program: the slave industry and its continued ramifications for society.

The ownership of slaves included and exceeded that of comfortable goods and genuine goods. The mortgages planted illustrate how the price of other people who were enslaved, the land on which they were forced to paint, and the houses they were forced to own were mutually constitutive. Richard Pares writes that “mortgages have become more and more common until, in 1800, almost all plantation debts were mortgages.” Slaves functioned as collateral for the debts of their masters, while intergenerationally executing under the debt of the master. Taxes on the products of plantations imported into Britain, as well as interest taxes paid to plantation lenders, provided benefits to Parliament and a source of profit to the monarch.

Mahogany, a valuable British import in the eighteenth century. It has been used for a wide variety of architectural programs and furniture, characterizing Georgian styles and regency. The forests were felled and crushed by slaves in Jamaica, Barbados and Honduras, among other British colonies. It is one of the few products in the triangular industry that continues to generate prices for those who have recently owned it.

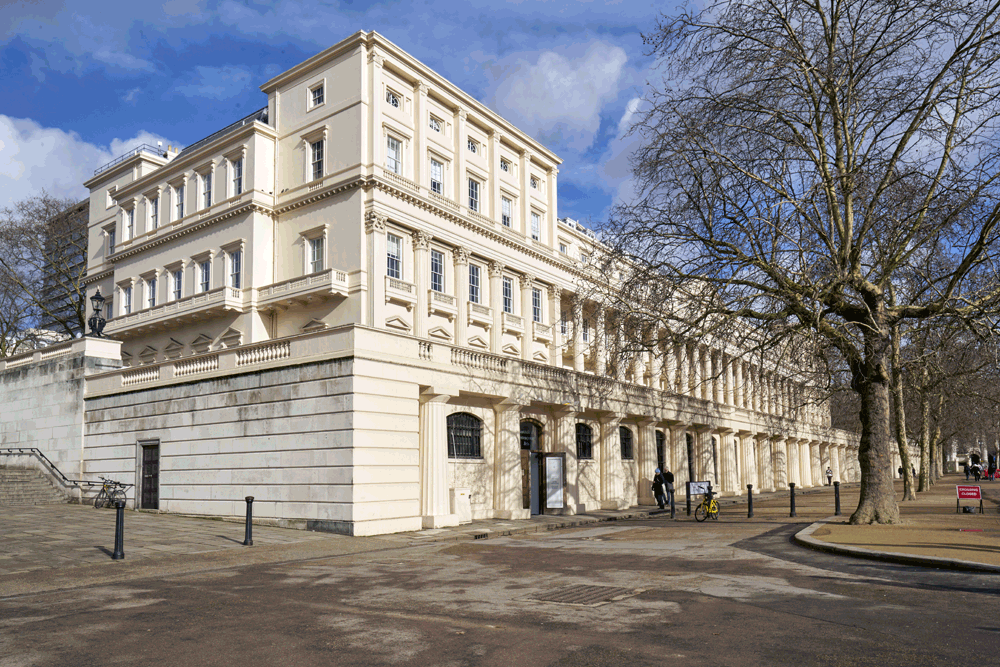

After taking the throne in 1820, George IV dismantled his residence, Carlton House, and his parents’ home, Buckingham House, combining elements to create Buckingham Palace. He built Carlton House Terrace between 1827 and 1832 on the former Site of Carlton House as a series of elite rental houses to generate a source of income for the Crown. All addresses of Carlton House Terrace still belong to Crown Estate, which has controlled Crown lands since 1760.

The elements that make virtually no sense in Rowland’s essay are scattered. Twenty-three brass shackles made in Birmingham in the 18th century rest on a heap on the floor of the lower gallery between glass beads. The painting is called Pacotille (2020), his call refers to the French word for “garbage”. These copper and brass were manufactured as African advertising items in Birmingham, Liverpool and Ireland, and were necessarily useless, but suitable as currency. Enslaved Africans were valued between 12 and 15 handles in the early 16th century through the Portuguese, and Europeans presented shackles as payment, but never accepted them as credits.

From there, Rowland connected the slave industry to the supply of time and to ICA itself. Since 1968, the ICA has been founded on 12 Carlton House Terrace, in a Crown-owned building since 1760. The site is officially the home of King George IV, who renovated the construction, adding 4 mahogany doors and a wooden handrail that takes it to the existing one in line with the gallery. Currently, there is a loan agreement based on several executives. The mahogany used in 18th-century furniture was cut and meerized through the tireless Caribbean staff for the refinement and cultivated tastes of the rich British. Rowland claimed those pieces of mahogany and called them art paintings, entitled Encumbrance (2020), which are provided for 1000 euros according to the piece through the ICA to Encumbrance Inc. a few weeks before the opening of the exhibition. The loan will not be refunded as long as mahogany is a component of the construction.

With that piece, Rowland is drawing on one of the cardinal principles of Afro-pessimism, a line of thinking which partly grew out of work by Jamaican scholar Orlando Patterson, who wrote that Blackness cannot be separated from slavery. According to Patterson, instead of defining enslaved Africans as forced or cheap labor, they are more acutely regarded as property. The enslaved were objectified in such a way that they were legally made an object to be used and exchanged like property, far from human, taking from their very being. Hence why Rowland has literally envisioned the transatlantic slave trade in the form of ready-made objects, which, like the slaves themselves, are here guided by land and property contracts.

European products exchanged for slaves were manufactured especially for this purpose. The shackles were used as one-way currency, which Europeans would offer as a means of payment but would never accept. The Portuguese decided the price of slave life between 12 and 15 shackles in the early 16th century. Birmingham was the leading manufacturer of copper shackles in Britain, before the city’s central role in the trade revolution. The British also used reasonable pearls acquired in Europe to buy slaves. Eric Williams describes the “triple stimulus of British industry” provided through the export of British products made for the acquisition of slaves, the processing of raw fabrics grown by slaves and the formation of new colonial markets for products manufactured in the Uk. the production of European goods for the slave industry supported domestic production markets. British industry in West Africa was considered a benefit of almost 100%.

What makes the black industry even more esteemed and vital is that almost nine-tenths of them are paid in Africa with British products and manufactures alone. ArrayArrayArray We do not ship any species or ingots to pay for Products from Africa, however bring gigantic amounts of gold; ArrayArrayArray On what facts, it can be said that industry with Africa is, so to speak, a benefit to the nation.

It’s certainly a food for thought, but Rowland unfortunately creates paintings that are virtually unreadable for a general public unfamiliar with black studies and art history. (A program of occasions that came with lectures through theorists K-Sue Park, Derica Shields, and Saidiya Hartman would have done a lot to elucidate Rowland’s intoxicating art, but canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic.) Deep and thoughtful exhibitions of black art are a bit more common, all of this may have been welcome, however the UK has only recently started interacting with black artists, let alone the black cliché and legacies of trafficking of slaves. . This means that the ICA wants to do more to contextualize Rowland’s paintings for its local audience.

Rowland and the Curators overestimated the public’s preference and commitment to a better perception of the political landscape, as even a paid visitor to the museum can tire of paintings as conceptual and rigorous as Rowland’s and disconnect. It is very unlikely that white British audiences will be much informed from a full text of documents, and it is even less likely to apply this text to elements as modest as Rowland’s. But the confusion even extends to a black British audience. As for Rowland’s paintings, friends and acquaintances have asked me what it all means. Blacks are entitled to varying degrees of opacity for their own safeguard and conservation resources such as time and emotional paintings. But who does Rowland intend to make his paintings readable, in reality, if it’s not for the themselves?