As a component of my studies for my book, Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord, I was looking for a report on the decades leading up to the Ram Janambhoomi-Babri Masjid crash in the 1980s, as well as Ayodhya’s politics. Shooting in 1990 that killed at least 16 kar sevaks. This incident and its widespread manipulation in the media through the RSS-VHP-BJP led the Hindu masses to unite their cause of “liberation” from Ram Lalla’s 16th-century idol. Babri Masjid.

These years of early mobilization Hindutva were what Jan Morcha, already popular in the region, left his mark as an intrepid and independent Hindi newspaper that adtached to the facts about RSS propaganda sold through the Hindi and English newspapers.

In fact, Jan Morcha is the only local newspaper to publish the figure of 16 killed in the November 2, 1990 shootings, when the Kar Sevaks defied curfew and attempted typhoon at the mosque. Most of the other diaries made headlines for provocatives such as “Blood-drenched Ayodhya” and “Blood Flows in Sarayu. “The reports themselves were filled with exaggerated and one-sided accounts of the cold-blooded “massacre” of kar sevaks through the UP government led through Mulayam Singh, which has been described as an anti-Ram and anti-Hindu temple.

“To date, no one has questioned this number of 16 dead. Some parliamentarians even cited our report in Parliament at the time,” said Suman Gupta, editor-in-chief of Jan Morcha’s Lucknow edition, who is running as a graphic reporter in the paper at the time.

Today, Jan Morcha, a Hindi newspaper published from Faizabad in Uttar Pradesh, is under pressure not only because of the diminishing attractiveness of his ideology and the advent of the corporate media, but also because of the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In her deep but hesitant voice, Sheetla Singh told me that the demanding situations facing the media fear Arnab Goswami and his Republic channel. “The questionable point is the ownership of the media and its appointments with the ruling elites,” she said.

As editor-in-chief of Jan Morcha for 53 years, 90-year-old Singh is arguably India’s oldest newspaper editor. Singh recently recovered from Covid-19 and returned to paintings because he believes it is better to “die fighting in the trenches. “”you hang your boots.

Jan Morcha, founded in 1956 through Mahatma Hargovind, a freedom fighter encouraged through Gandhi’s nonviolent struggle for independence. Strongly rooted in socialist ideals, the survival of the cooperative newspaper in the 21st century is miraculous. And even if the small team of 12 to 15 more people withstand crises, having weathered many storms, the pandemic turns out to be a war for the newspaper’s survival.

The first time I went to Jan Morcha’s workplace was on a very hot summer afternoon in 2016. Early in the day, an experienced journalist from a classic Hindi newspaper presented his unwanted but insightful recommendation in the newspaper. “Look, there have been camps among the faizabad-Ayodhya newspapers. The first is the Ram-bhakt field, to which virtually all newspapers belong. Some national newspapers and those of Jan Morcha make up the Ram-virodhi camp,” he told me as he had a coffee at the Shan-e-Awadh Hotel, which is located in Faizabad-Ayodhya, which was once the Broadway Hotel in Srinagar: the place to go for visiting journalists.

Throughout the turbulent years of the Ram Temple movement, Jan Morcha published balanced media coverage, the myth propagated through VHP spread in the top newspapers. A small example of this nuanced and objective technique is seen in its persistent use of words such as “Ram Janambhoomi-Babri Masjid” and the “contested site”, while most Hindi newspapers have followed the VHP coin of “Ram Janambhoomi” and “contested structure” to refer to the Babri mosque.

He continues this approach, as evidenced by his policy of last year’s Supreme Court verdict that attributes the disputed site of the Babri mosque to Hindu parties. vernacular media.

Until the 1990s, Jan Morcha was one of the most popular newspapers in Faizabad and neighboring districts, but for more than 3 decades, with major newspapers launching their local editions and the broader disorders derived from the commodization of information, the flow of information. newspaper has fallen. Of 4 editions, he published only two, in Faizabad and Lucknow, and a third edition released by Bareli through a franchise.

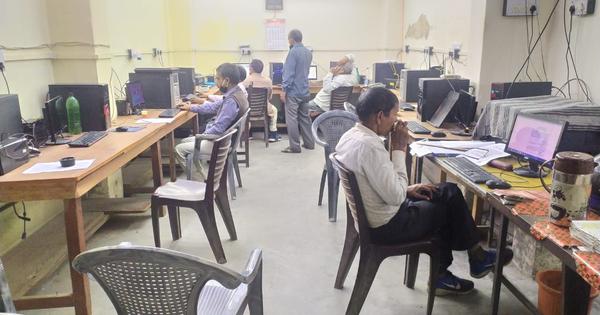

Although the paper’s heyday is over, its workplace is hard to answer with a few questions. Located in one of the oldest parts of Faizabad, it [K1] is in a decrépit state, with cracked doors, exposed electrical cables, old furniture and obsolete non-public computers [K2].

But come in, [K3] and immediately feel the incomparable atmosphere of a wording. On the first floor, the newspaper helps keep its files that, for lack of resources, have remained unattended for many years. The segment bears witness to its main ideals and its rich world view. Jan Morcha’s piles of yellowish, dust-soaked newspapers provide as much information about the Awadh region as it is about the country and the world.

Sheetla Singh joined the newspaper at the age of 26. In the following decades, the newspaper known with communist ideology. During the 1962 war with China, its publisher Hargovind qualified with the National Security Law [K4] and sent to criminal by an editorial. The government later withdrew the tax and released him.

Infused with socialist customs, Sheetla Singh has shaped the newspaper’s view of the journalism creed as a “public good” and news as a “public utility. “”We can make mistakes, but we don’t do business and delete information,” he said. . ” You can check our functions given the scarcity of resources, but no one can suspect our intentions.

It was this commitment that served the newspaper well over the years and helped the onslaught of the circle of newspapers and family media companies. “We don’t sell ads in the paper,” Sheetla Singh said. “Our effort is to provide data and insights that help others perceive their world faster and broader. And despite our limitations, I think our readers perceive it and respect the newspaper for it.

Singh may be right about Jan Morcha’s strengths because, despite the presence of primary Newspapers in Hindi such as Dainik Jagran, Amar Ujala, Hindustan and Rashtriya Sahara, the newspaper remains popular in villages and towns in the Awadh region. Vijay Kumar, a farmer from nearby Mankapur, said he kept reading Jan Morcha because he provides the fact and doesn’t cause a sensation like other newspapers. “Jan Morcha understands local data that other newspapers don’t broadcast, and this doesn’t fool the reader,” he said.

“Jan Morcha has an intellectual influence and a critical technique based on progressive politics,” said Professor Anil Singh of Saket Degree College in Faizabad. “This gives way to democratic rights considerations that are recently under threat. In our context, I believe that Jan Morcha can be the Telegraph and how it contradicts the majority’s agenda.

However, there is also a critique of Jan Morcha, who has lost the interest of man, and its dissemination is limited to the intellectual and liberal circles of the left.

KP Singh, 59, is the editor of Jan Morcha’s Faizabad edition. During the pandemic, he also contracted Covid-19 and was unable to move on to paintings for about a month. When I spoke to him recently, he was recovering from dengue fever.

“We’re a team of six here and we’re all multitasking,” he said in a video call. “Sheetla ji provides us with the general editorial direction of the day and takes care of the publisher. Our independent reporters in the domain” send us news via WhatsApp, which become articles through here. It is not easy to take out the document, however, we have adapted to the demanding situations and the pandemic will not last forever. Suman Gupta and KP Singh are veteran newscasts and have proven to be trusted hands in the newspaper.

“Shortly after the blockade was announced, we made the decision to reduce the pages from twelve to eight. This helped us continue to publish the blockade with our existing newspaper inventory,” Gupta said. “The other thing we’ve done is decrease the number of color pages,” he added.

These measures would possibly help the pandemic to some extent and are unlikely to be effective for the long-term survival of the document. Classified UP government ads have been reduced to a network. companies, politicians and local businesses. ” Everyone needs bright paper and multicolored prints, which we don’t have,” says Ram Teerath, marketing director at Jan Morcha. “Most of our advertising profits come from small classified ads and small businesses at festivals. “

Jan Morcha’s flow was around 20,000 before the pandemic. “People were afraid to read the papers because of the coronavirus. And with the economy stagnant, our flow has fallen by 15% since March,” Teerath said.

Can Jan Morcha succeed over the latest crisis?Sheetla Singh said: “There has never been a greater challenge. If existing situations persist, I don’t see how we can survive. “Suman Gupta is more optimistic. ” We can succeed in this crisis with the highest editorial quality, monetary prudence and through the expansion of our success through generation and innovation,” he said.

However, in the absence of new resources, the survival of daily life is threatened, what the newspaper most desires is new blood and new energies, for example, it has a rudimentary website, has virtually no presence on social networks.

According to KP Singh, “Jan Morcha was not rejected by readers. People turn to him to check vital news. It helps keep alive the area that is rapidly shrinking for a policy of choice that is progressive and secular. Indeed, in the age of mail – the truth and the plettive of dubiously funded media, the newspaper’s continued survival is a ray of hope for democratic forces in the region and beyond. But if intelligent journalism is a prerequisite for an informed audience, it turns out that lately it exists it is not soft at the end of the tunnel.