“o. itemList. length” “this. config. text. ariaShown”

“This. config. text. ariaFermé”

Stay informed at a glance with top 10 stories

(Bloomberg) – Just before planting began in May, Abdullahi Hassan Wagini visited a neighbor’s farm in northern Nigeria to talk about box preparation, which followed led him to give up his 25-year-old life.

As the two men spoke, bandits on motorcycles opened fire on them. Wagini, 62, controlled to escape, while his friend stayed to protect his livestock. He discovered dead in a pool of blood, his cows disappeared.

These ruthless killings are not unusual in a country where painting the land can be a harmful profession due to long-standing ethnic and devout tensions and, more recently, organized crime, that is, when farmers have already had to deal with floods or droughts. this is now affecting agriculture at a time when Nigeria wants it most.

The concept of food security, as a reliable source of livelihood for a population, resonates worldwide in the era of interrupted coronaviruses and chains of origin. In Africa’s largest economy, it has many dimensions.

The pandemic has caused food costs to sod in a country that imports more than a tenth of its food supply. Two-thirds of the population is engaged in some form of agriculture. However, the maximum number of farmers cannot invest in quality seeds and fertilizers. irrigation and machinery, all of which have limited agricultural production. For many, climate replacement has made their stage even more terrible.

While farmers of which there were once fertile northern regions have sought new mass paintings, those left face gangs seeking extortion in cash by holding people, land and livestock in exchange for ransom. to open a grocery store, he said by phone from his village of Katsina. The state is part of Nigeria’s bread basket, a center of rice, wheat and sorghum, a cereal used as food and fodder for animals.

“The security scenario is not favorable,” said Wagini, a retired government worker who relied on agriculture to build his source of income and feed him, his two wives and 17 children. “This has been a major setback for agriculture in the region. . “

Demanding situations come at a time when the world is expected to revel in a strong build-up of food confidence due to the consequences of Covid-19. Up to 132 million more people worldwide can go hungry this year.

Around the world, fears of a full-size food crisis have increased, as some primary cereal exporters have limited shipments due to the pandemic, exposing the vulnerability of countries that rely on foreign industry for their commodities. aim to increase their domestic food production.

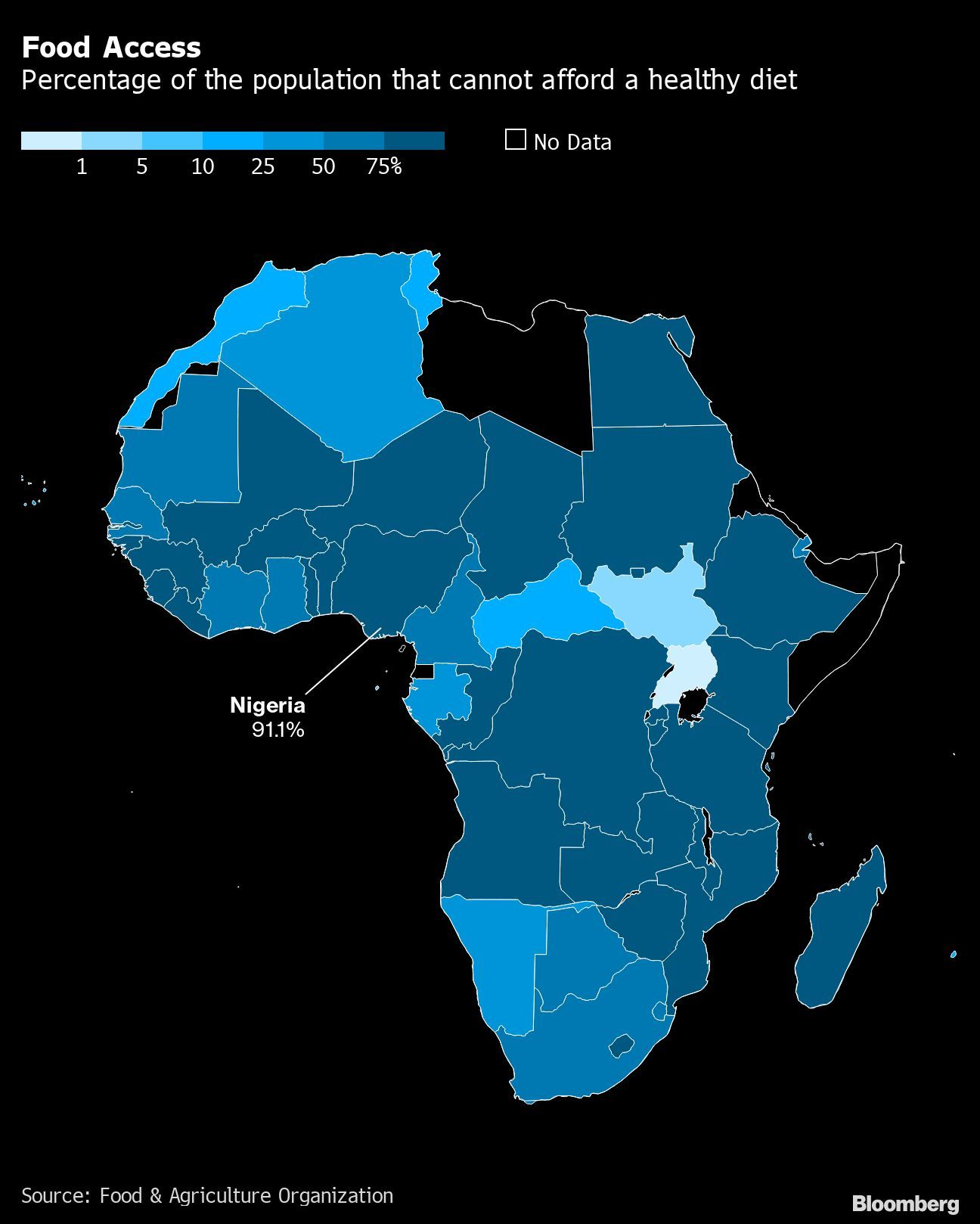

With a population of two hundred million, Nigeria is the most populous country on the continent exposed to a lack of food confidence in the world. Producing food at home is more vital because importers are suffering to access dollars to pay for shipments after the fall. oil costs that have undermined foreign exchange reserves. “We are heading for hunger and famine,” Niger State Governor Abubakar Sani Bello warned in April.

“The country is by no means self-sufficient in food production,” said Nnamdi Obasi, Nigeria’s senior advisor at the International Crisis Group in Abuja, the capital. “So when the foreign food import chain is disrupted and agriculture is also disrupted locally, it is a very worrying mix for the country. “

In the 1960s, Nigeria produced enough food of its own and was the world’s largest manufacturer of crops such as peanuts and palm oil. Subsequent governments prioritized the oil industry over investments in agriculture.

President Muhammadu Buhari, who was born and raised in Katsina state, has been looking to orchestrate a renaissance since his election in 201 five by reducing imports of rice and other food products while boosting mechanized agriculture. The purpose is to create five million jobs in agriculture and raise 100,000 hectares of new agricultural land in each of Nigeria’s 36 states. The president’s mantra is “we produce what we eat and eat what we produce. “

Improvements have already been made to rice and cassava production and the covid-19 effect has given new impetus, but while Buhari suggested farmers produce more, years of underinversion left them ill-equipped. they could be if farmers had better seeds, fertilizers and planting practices, said Kenton Dashiell, deputy director general of the International Tropical Agriculture Institute in nigeria’s Ibadan city.

Meanwhile, Buhari ordered the central bank to avoid offering foreign exchange for the importation of food and fertilizer as a component of ongoing efforts to bring local agricultural production to life and maintain dollar shortages.

Constant warming with phenomena has also turned some of the once green northern fields into a desert amid water scarcity. In the northeastern state of Borno, the Sahara Desert is invading at a pace of one kilometer consistent with the year, the Nigerian government estimated in 2018.

“One of the main disorders in Nigeria is low irrigation capacity and this will exacerbate climate change,” said Kwaw Andam, director of Nigeria’s country program at the International Food Policy Research Institute, or IFPRI, in Abuja.

Although movement restrictions to control Covid-19 infections have exempted agriculture, the measures remain food services, shipping and processing. As a result, Nigeria’s agricultural production has fallen by about 13%, and genuine adjustment of the food source will occur by the end of next year, IFPRI estimates.

About 85% of Nigerians have experienced value increases since the Covid-19 epidemic, with the effect of scarcity aggravated by a decrease in the burden of the local currency, naira. The burden of imported food has increased by 28% compared to a year ago, forcing many Nigerians to replace their diets. The number of others suffering from lack of food confidence could increase to about 23 million this year, a spokesman for the UN World Food Programme said.

But even as costs begin to fall as the pandemic yields and chains of origin are restored, the risk of violence involving sectarian teams and gangs of criminals remains.

The federal government has deployed troops to attack security, it has not stopped the wave of farmers defecting from the region in recent years. The number of others who left their lands in the northern states of Katsina, Kaduna, Jigawa and Zamfara doubled in 2020. , according to the Farmers’ Association of Nigeria.

In fact, the agricultural regions of the north and the central belt are home to a range of conflicts ranging from long-standing rivalries over land and water resources to Islamist militants.

In the northeast, the government has been fighting Boko Haram for more than a decade and, more recently, opposed a dissident organization aligned with the Islamic State. Other jihadist teams would possibly be making raids in the northwest, where there are also armed youths. Teams of people raiding villages, borrowing cattle and kidnapping others for ransom.

In general, tens of thousands of hectares or arable land have been destroyed or become inaccessible, thousands of farm animals and sheep have been stolen and markets have been disrupted.

Wagini, the farmer in Katsina state, said local cassava production, a tuber, had plummeted as a result of bandit attacks, while men with machetes invaded nearby forests and destroyed all planted crops only to prevent others from developing. Commodity costs have more than quadrupled due to scarcity. More and more people stay home, locking up their animals for fear of being attacked.

Banditry also reduces rice production, the maximum that feeds on grains in Nigeria. In Kebbi state, the country’s rice growing center, many farmers have stopped going to their fields for fear of an attack, farmer Rikotu Isha said. , flooding thousands of hectares of land and houses and killing at least six other people at the end of August.

“My circle of relatives and I live off last year’s produce, but this is coming to an end, which means we’re all going to be hungry soon,” Isha said on the phone. “Armed banditry destroys our income. Agriculture is the source of our livelihood. If we can’t grow, we’re hungry. “

Since his neighbor’s murder, Wagini has visited his estate only once, believes gunmen who killed, maimed, kidnapped and raped in the region were left unpunished. The government has assisted farmers in mitigating the effects of the attacks said.

In July, other farmers in the village took up the threat of returning to their farms. For Wagini, it’s time to move on, he said. “I can’t threaten my life by going to the farm. “

– With Jeremy Diamond

For more items like this, visit bloomberg. com.

Subscribe now to forward with the ultimate source of reliable business news.

© 2020 Bloomberg L. P.