Supported by

Send a story to any friend.

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift pieces to offer per month. Anyone can read what you share.

By Patricia Cohen

Patricia Cohen, economic correspondent in London, and Cristian Movila, photojournalist, reported from Prundu and Constanta, Romania.

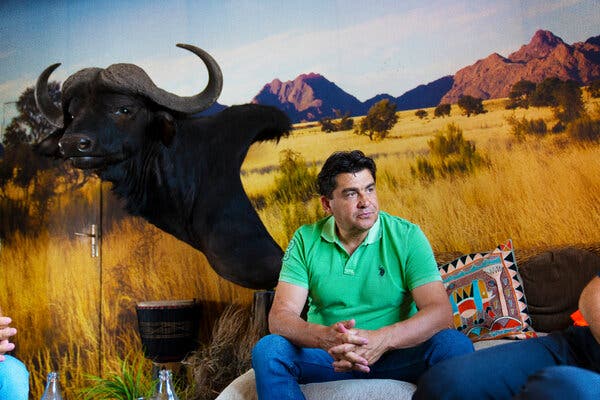

Stopping at the edge of a barley box at his farm in Prundu, 30 miles from Bucharest, the Romanian capital, Catalin Corbea pinched a flower with a bristly stem, rolled it in his hands, then stuffed a seed into his mouth and bit it.

“Another 10 days to two weeks,” he said, explaining how much time he spent before harvest in a position for harvest.

Mr. Corbea, a farmer for almost 3 decades, has rarely experienced a season like this. The Russians’ bloody invasion of Ukraine, a breadbasket for the world, sparked turmoil in global grain markets. Coastal blockades have trapped millions of tons of wheat and corn inside Ukraine. With famine ravaging Africa, the Middle East and Asia, a frantic race towards new suppliers and shipping route options is underway.

“Because of the war, there are opportunities for Romanian farmers this year,” said Mr. Corbea, an interpreter.

The question is whether Romania will benefit from this by creating its own agricultural sector while helping to fill the food gap left in landlocked Ukraine.

In many ways, Romania is well positioned. Its port of Constanta, on the west coast of the Black Sea, has provided a critical, albeit small, transit point for Ukrainian grain since the beginning of the war. Romania’s own agricultural production is dwarfed by Ukraine’s, but it is one of the Largest Cereal Exporters in the European Union. Last year it shipped 60% of its wheat abroad, basically to Egypt and the rest of the Middle East. This year, the government allocated 500 million euros ($527 million) to agriculture and production maintenance.

However, this Eastern European country faces many challenges: its farmers, although they benefit from higher prices, face skyrocketing prices for diesel, insecticides and fertilizers. exports while hampering Romania’s efforts to get Ukraine to circumvent Russian blockades.

However, even before the war, the global food formula was under pressure. COVID-19 and supply chain blockades have pushed up fuel and fertilizer prices, while periods of brutal drought and unseasonal flooding have reduced harvests.

Since the war began, about two dozen countries, in addition to India, have tried to build their own food materials by restricting exports, exacerbating global shortages. This year, droughts in Europe, the United States, North Africa and the Horn of Africa have weighed more heavily on crops. In Italy, water was rationed in the agricultural valley of the Po after the point of the river descended enough to reveal a barge that had sunk in World War II.

The rain was not as heavy in Prundu as it was in M. Corbea would have liked it, but just the right time when she arrived. He crouched down and picked up a handful of dark, damp soil and stroked it. Said.

Thunderstorms are forecast, however, this morning the likely endless hairs of barley under a cloudless cerulean sky.

The estate is a matter of circle of relatives, involving M’s two sons. Corbea and her brother. They grow about 12,355 acres, growing rapeseed, corn, wheat, sunflower and soybeans, as well as barley. In Romania, yields are not expected to reach record cereal production of 29 million metric tons from 2021, however, the harvest outlook remains good. with many products to export.

A large-scale clash. The Russian invasion of Ukraine had a domino effect around the world, adding to the problems of the inventory market. The crash has sent fuel costs and product shortages soaring, and prompted Europe to reconsider its reliance on Russian energy sources.

Global expansion is slowing. The fallout from the war has hampered major economies’ efforts to emerge from the pandemic, injecting new uncertainty and undermining economic confidence around the world. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has warned that the war is fuelling immediate inflation; Global expansion is expected to slow to 2. 9% this year, from 5. 7% in 2021.

Energy costs are rising. Oil and fuel costs, which were already rising as a result of the pandemic, have risen since the beginning of the conflict. The worsening confrontation has also forced countries in Europe and elsewhere to reconsider their reliance on Russian power and seek sources of choice.

The Russian economy is facing a slowdown. Although pro-Ukrainian countries continue to adopt sanctions against the Kremlin in reaction to its aggression, the Russian economy has so far avoided falling into a crippling collapse thanks to capital controls and emerging interest rates. But the head of Russia’s central bank warned that the country would most likely face a sharp economic slowdown as its inventory of imported goods and currencies was low.

Trade barriers are emerging. The invasion of Ukraine also unleashed a wave of protectionism as governments, desperate to protect goods for their citizens amid shortages and emerging prices, erected new barriers to prevent exports. But the restrictions make products more expensive and harder to find.

The Ravitaillement. La war has driven up food costs in East Africa, a region that relies heavily on wheat, soybean and barley exports from Russia and Ukraine. Meanwhile, Western leaders have accused Russia of militarizing the world’s food source with its blockade of Ukrainian cereals.

The prices of a must-have metal are skyrocketing. The price of palladium, used in the exhaust systems of cars and mobile phones, has soared amid fears that Russia, the world’s largest exporter of the metal, could be cut off from world markets. nickel, Russia’s key export, has also increased.

Mr. Corbea slips into the driver’s seat of a white Toyota Land Cruiser and drives through Prundu to make a stop at the cornfields, which will be harvested in the fall. He has been mayor of the city of 3500 inhabitants for 14 years and greets one and both passing car and pedestrian, adding his mother, who stands in front of his space when he passes. The trees and red and pink roses that line the street have been planted and maintained by M. Corbea and its workers.

It said it employs another 50 people and generates a turnover of €10 million consistent with the year. In recent years, the farm has invested heavily in generation and irrigation.

Amid rows of leafy green corn, a long central pivot irrigation formula stands like a skeletal pterodactyl with outstretched wings.

Due to emerging costs and increased production of the irrigation apparatus he has installed, Mr. Corbea said he expects profits to rise to 5 million euros, or 50 percent, in 2022.

The costs of diesel, insecticides and fertilizers have doubled or tripled, but, at least for now, the costs that M. Corbea said he can get for his grain more than offset the increases.

But costs are volatile, he said, and farmers want to make sure long-term gains cover their long-term investments.

The calculation has paid off for other major players in the sector. “Profits are highest, you can’t imagine, the biggest of all time,” said Ghita Pinca, CEO of Agricover, an agribusiness company in Romania. Long-term growth, he said, is based on increased investment through farmers in irrigation systems, garage services and technology.

Some small farmers like Mircea Chipaila have had more difficult times. Mircea grows barley, corn and wheat on 1975 acres in Poarta Alba, about 150 miles from Prundu, near the southeastern tip of Romania and along the canal connecting the Black Sea to the Danube.

A drier climate means that its production will fall to last year. And with fertilizer and fuel costs on the rise, he said, he expects his profits to fall as well. Ukrainian exporters have reduced their costs, which has put pressure on what they sell.

Mr. Mircea’s farm is about 15 miles from the port of Constanta. Normally a major hub for trade and grain, the port connects landlocked countries in central and southeastern Europe such as Serbia, Hungary, Slovakia, Moldova and Austria with Central and East Asia and the Caucasus region. Last year, the port treated 67. 5 million tons of goods, more than a third of which were cereals. Now that the port of Odessa is closed, some Ukrainian exports are passing through the Constanta complex.

The train cars, with the “Cereal” seal on the sides, dumped Ukrainian corn on underground conveyor belts, sending clouds of swollen dust last week to the terminal operated by U. S. food giant Cargill. At a dock operated by COFCO, China’s largest agricultural and food processor, grains loaded into a shipment from one of the huge silos lining its docks. At COFCO’s front door, trucks carrying Ukraine’s unique blue and yellow striped flag on their plates waited for their grain shipments to be inspected before unloading.

During a visit to Kyiv last week, Romanian President Klaus Iohannis said that since the invasion began, more than a million tons of Ukrainian grain had passed through Constanta to places around the world.

But logistical disorders prevent you from making the trip with more grain. The track gauges of Ukrainian trains are wider than those of other parts of Europe. Shipments will have to be transferred at the border to Romanian trains, or each car will have to be lifted from a Ukrainian landing gear. and wheels to a wagon that can be used on Romanian tracks.

Truck traffic in Ukraine has slowed through safeguards at border crossings, for days, as well as fuel shortages and broken roads. Russia has focused on export routes, according to the British Ministry of Defense.

Romania has its own transit problems. High-speed rail is rare and the country has an extensive road network. Constanta and the surrounding infrastructure also suffer from decades of lack of investment.

Over the past two months, the Romanian government has spent money cleaning up piles of rusty train cars and rehabilitating abandoned tracks after the fall of the communist regime in 1989.

However, trucks entering and leaving the port from the road will have to pass through a single-lane carriageway. An assistant holds the door, which must be lifted for each vehicle.

When most of the Romanian harvest begins to arrive at the terminals in the next two weeks, congestion will worsen significantly. Every day between 3,000 and 5,000 trucks will arrive, mishap of kilometers on the road leading to Constanta, said Cristian Taranu, general terminal manager through the Romanian port operator Umex.

M. Mircea Farm is less than a 30-minute drive from Constanta. But “during peak periods, my trucks wait two or three days” just to enter the port complex so they can unload, an interpreter said.

This is one of the reasons why he is less positive than Mr Corbea about Romania’s ability to take advantage of agricultural and export opportunities.

“Port Constanta is not prepared for such an opportunity”, Mr. Mircea. “They don’t have the infrastructure. “

Advertising