Alaska medical providers no longer want to report patients’ COVID-19 cases to states, but there are new needs to report other emerging illnesses and health issues, under new regulations that went into effect earlier this month.

COVID-19 goes unreported for two main reasons, said Louisa Castrodale, an epidemiologist with the Alaska Division of Public Health.

While regulations still have a blanket mandate to report “new” diseases, COVID-19 no longer fits that description, he said. What’s more, much of the diagnosis is made using home tests done by patients themselves rather than providers, making follow-up difficult, he noted.

Mandatory reporting of COVID-19 cases remains in place for laboratories under the new regulations. While this data may not give exact totals, it will provide insight into how the disease spreads in communities, Castrodale said.

“We need to use knowledge in a meaningful way to inform ourselves about trends,” he said.

Infections caused by the virus, called RSV, are not unusual respiratory situations that cause serious problems, especially in infants and young children. High hospitalization rates in rural Alaska for RSV infections have been linked to poor water and sanitation and overcrowded housing.

So far, RSV cases in Alaska have been tracked in some way, but this has largely happened outside of the public fitness reporting system, Castrodale said. Regional rescue personnel and fitness providers have been intensively tracking RSV outbreaks due to the limited source of pediatric hospital beds in affected areas, he said.

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in southwest Alaska has long had rates of childhood hospitalization for RSV infections in the country, up to seven times the national average, according to medical researchers. Preventive measures have reduced those hospitalizations over the years, but childhood hospitalization rates are still more than three times the national average, according to Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corp. , the tribal regional physical care provider.

Castrodale said there are high hopes for three types of new RSV vaccines developed for children and adults. Periodic reports, along with new vaccines, help health officials monitor long-term changes, he said.

“We’re going to have a concept of how to track this in the future,” he said.

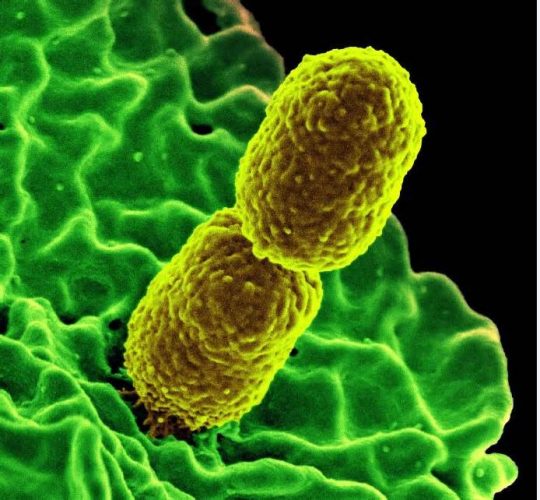

Another notable update to the reporting requirements is the updated wording on antibiotic-resistant organisms considered to be of national importance.

They also come with infections with carbapenem-resistant organisms, or CROs. This gave the impression that in Alaska; Six cases have been documented in healthcare facilities in 2022 and this year.

The new regulatory formulas are more flexible, with a broader scope, suitable at a time when more pathogenic organisms are being discovered that do not respond to drugs, Castrodale said. “These insects extend resistance,” he said. Just not knowing what it is. “

Additional changes to public health reporting requirements come with language about blood lead levels. Instead of setting a constant numerical threshold for reporting, which may need to be adjusted in the future, the new requirements link Alaska’s reporting to national criteria, Castrodale said. Criteria defining “high” blood lead levels have become stricter over time; More recently, in 2021, they were reduced from five micrograms per deciliter to 3. 5 micrograms per deciliter.

Alaskan fitness officials are already aware of the need for more testing for lead levels in children’s blood. Testing has declined especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an epidemiological bulletin published last year.

The state’s requirements for public health reporting are updated every few years, Castrodale said. The updates come with a regulatory process that takes eight to twelve months, he said.

GET YOUR MORNING NEWSPAPERS IN YOUR INBOX

by Yereth Rosen, Alaska Beacon September 20, 2023

Alaska medical providers no longer want to report patients’ COVID-19 cases to states, but there are new needs to report other emerging illnesses and health issues, under new regulations that went into effect earlier this month.

COVID-19 goes unreported for two main reasons, said Louisa Castrodale, an epidemiologist with the Alaska Division of Public Health.

While regulations still have a blanket mandate to report “new” diseases, COVID-19 no longer fits that description, he said. What’s more, much of the diagnosis is made using home tests done by patients themselves rather than providers, making follow-up difficult, he noted.

Mandatory reporting of COVID-19 cases remains in place for laboratories under the new regulations. While this data may not give exact totals, it will provide insight into how the disease spreads in communities, Castrodale said.

“We need to use knowledge in a meaningful way to inform ourselves about trends,” he said.

Infections caused by the virus, called RSV, are not unusual respiratory situations that cause serious problems, especially in infants and young children. High hospitalization rates in rural Alaska for RSV infections have been linked to poor water and sanitation and overcrowded housing.

So far, RSV cases in Alaska have been tracked in some way, but this has largely happened outside of the public fitness reporting system, Castrodale said. Regional rescue personnel and fitness providers have been intensively tracking RSV outbreaks due to the limited source of pediatric hospital beds in affected areas, he said.

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in southwest Alaska has long had rates of childhood hospitalization for RSV infections in the country, up to seven times the national average, according to medical researchers. Preventive measures have reduced those hospitalizations over the years, but childhood hospitalization rates are still more than three times the national average, according to Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corp. , the tribal regional physical care provider.

Castrodale said there are high hopes for three types of new RSV vaccines developed for children and adults. Periodic reports, along with new vaccines, help health officials monitor long-term changes, he said.

“We’re going to have a concept of how to track this in the future,” he said.

Another notable update to the reporting requirements is the updated wording on antibiotic-resistant organisms considered to be of national importance.

They also come with infections with carbapenem-resistant organisms, or CROs. This gave the impression that in Alaska; Six cases have been documented in healthcare facilities in 2022 and this year.

The new regulatory formulas are more flexible, with a broader scope, suitable at a time when more pathogenic organisms are being discovered that do not respond to drugs, Castrodale said. “These insects extend resistance,” he said. Just not knowing what it is. “

Additional changes to public health reporting requirements come with language about blood lead levels. Instead of setting a constant numerical threshold for reporting, which may need to be adjusted in the future, the new requirements link Alaska’s reporting to national criteria, Castrodale said. Criteria defining “high” blood lead levels have become stricter over time; More recently, in 2021, they were reduced from five micrograms per deciliter to 3. 5 micrograms per deciliter.

Alaskan fitness officials are already aware of the need for more testing for lead levels in children’s blood. Testing has declined especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an epidemiological bulletin published last year.

The state’s requirements for public health reporting are updated every few years, Castrodale said. The updates come with a regulatory process that takes eight to twelve months, he said.

GET YOUR MORNING NEWSPAPERS IN YOUR INBOX

Alaska Beacon is owned by States Newsroom, a network of grant-funded news bureaus and a coalition of donors as a 501c public charity (3). Alaska Beacon maintains its editorial independence. Please contact editor Andrew Kitchenman if you have any questions: info@alaskabeacon. com. Follow Alaska Beacon on Facebook and Twitter.

Yereth Rosen came to Alaska in 1987 to work for the Anchorage Times. He has reported for Reuters, Alaska Dispatch News, Arctic Today and organizations. It covers environmental issues, energy, climate change, natural resources, economic and industry news, health, science and Arctic concerns. In her free time, she enjoys skiing and watching her son’s hockey games.

DEMOCRACY TOOLKIT

Alaska Beacon is an independent, nonpartisan news organization that aims to link Alaskans to their state government. Our news hunters report quite bravely on the other people and interests of that state policy.

Our stories can be republished online or in print under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4. 0 license. We ask you to modify them according to taste or abbreviation, to provide proper attribution and a link to our website.