It was August 8 when I tested positive. He had just returned from work and was at home in Naha, a town in Okinawa Prefecture. I had a mild temperature and my throat was weird.

An antigen showed my suspicions.

At the time, Okinawa was recording 5,000 coronavirus cases a day. Hospitals were under siege and, to ease the pressure on the medical system, the government advised young people to stay at home and recover. I logged my medical history online, took medication, and waited.

He had won 3 doses of vaccine. I also knew that colleagues my age had temporarily recovered from COVID, so I assumed everything would be fine.

Five days later, my temperature returned to normal, but my fight was just beginning.

My fever and symptoms of lack of blood usually went away, but I found that simply getting up while cooking in my kitchen made my center speed up and I felt chills.

When I researched my symptoms online, I discovered articles that other people had written in English about long COVID. They told how, after recovering from an infection, they experienced what is known as postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a buildup in the center. rhythm that only occurs when standing.

I knew that COVID can just tire other people out and that it can have an effect on taste and smell, but this data on POTS was new to me. None of the doctors I visited had told me about it.

I needed to find someone who could help me, but I didn’t know where to look.

It’s now September. A month had passed and I didn’t feel any better. My friend got married in October, but I couldn’t see myself recovering until then, so I sent him my apologies.

Before contracting COVID, I had a very active lifestyle, with frantic days at the office, interrupted weekends at the gym, or hikes in the nearby mountains. All that had changed.

My blood oxygen levels were normal, but my average frequency was over 130. Every time I got up, my pulse quickened. When I went to bed, it went back down to 80.

An electrocardiogram did not uncover anything abnormal. The doctor prescribed beta-blockers (medications that lower blood pressure), but my heart rate exceeded 115 when I was standing. Responsibilities as simple as cooking and showering were exhausting.

On weekends, I would stay home or go to the local supermarket, moving around like a turtle.

During the week, I was able to paint from home, but I think about the many other people suffering from my symptoms who didn’t have the option to paint remotely.

Another echocardiogram check was normal. The doctor confided in me that I had nothing to worry about. The diagnosis that my symptoms were due to weight loss and since beta-blockers had not been effective, I had to stop taking them.

I stopped taking medication and my symptoms got worse. The doctor gave me the treatment.

Another doctor specializing in classical herbal medicine couldn’t either.

Different doctors told me other things. Hospital expenses piled up, as did my sense of hopelessness.

I spent almost every moment of my free time researching the long COVID online, and what I discovered only added to my anxiety. I had trouble sleeping at night.

Finally, I discovered longCOVID. jp, a tour by Kouichi Hirahata, a Japanese doctor who performs medical examinations on patients suffering from post-COVID illnesses.

Based on their findings, I should try the following treatment. I must emphasize that the effects are based solely on my own experience and do not deserve to be taken as evidence that any of those remedies are valid and effective.

Japanese doctors have been applying abrasive epipharyngeal treatments for more than a century to treat chronic inflammation of the nose and throat. They insert a stick-shaped device into the nose or mouth and use it to apply zinc chloride to the affected area. It regularly takes 20 sessions to complete the treatment.

My first 3 sessions were painful and made me cough up bloody phlegm. But as the sessions progressed, the pain and blood subsided and during the ninth session I no longer bled.

That is, if my remedies helped me or if my condition simply improved over time, but my core frequency gradually stabilized and I was able to decrease my medication.

The regimen of the remedy had given me a much more positive attitude. I no longer felt lost or afraid. I’m still on medication and I wouldn’t say I’m one hundred percent better, but now I’m at the point where I can go back to conducting outdoor interviews.

One thing I have learned is that the mental consequences of this disease outweigh the physical consequences.

Much is still unknown about long COVID. There is no definitive remedy and no way to know how long it will take a user to recover. For some, it takes months. For others, the debilitating illness can last for years. It is only used herbal to fight emotions of hopelessness.

In fact, I’m one of the lucky ones. Other people are wasting their jobs. Some contract this disease while raising a child alone.

There is no outpatient treatment for long COVID in Okinawa. The prefecture is pushing a formula in which private doctors and local clinics can treat the sick, with the help of general hospitals if necessary.

Some doctors say it’s too hard to get data on long-term COVID and that there are enough medical staff to treat it.

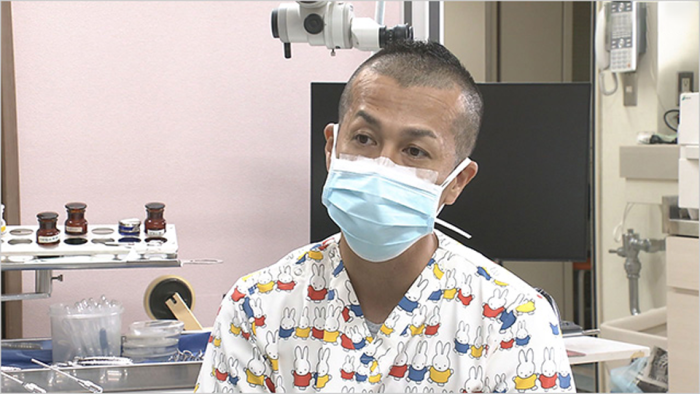

Dr. Shingaki Kota, director of a clinic in Okinawa that provides epipharyngeal abrasive treatment, says he can’t say for sure that the treatment is effective. “But there is a developing evidence framework on this and other approaches to long COVID,” he says. “So I’d like them to at least be noticed as a possible course of action. “

The Okinawa government claims that “between 10% and 20% of all cases result in prolonged COVID. “Since another 500,000 people in this prefecture fell ill in October, this means that up to 100,000 may now be suffering from prolonged COVID. They want more data about the disease, but they want more than that. They want direct help.